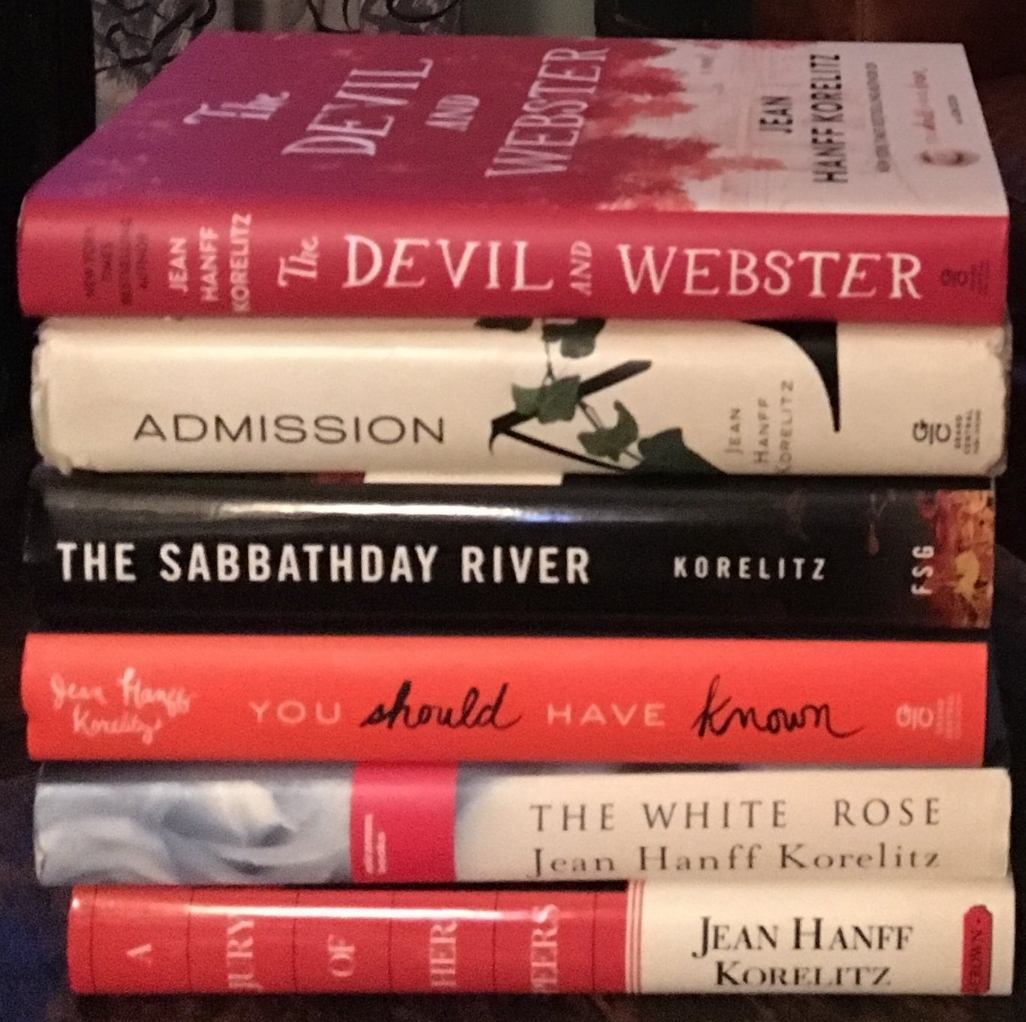

THE DEVIL AND WEBSTER

THE DEVIL AND WEBSTER is now out in paperback

Order it here

Long listed for the first Aspen Words Literary Prize

“Not since Randall Jarrell’s comic masterpiece PICTURES FROM AN INSTITUTION, published in tamer times (1952), has there been such an entertaining portrayal of neurotic academia. Jean Hanff Korelitz deftly reveals how self-absorption can be simultaneously horrifying and hilarious.”

The Guardian (UK) asked me to list my 10 favorite campus novels.

NPR (Maureen Corrigan)

A few days ago, one of my students asked me what I was reading, so I told her about Jean Hanff Korelitz's new novel, called The Devil and Webster. My student's eyes got wider as I finished lightly summarizing the plot, and she said, with some concern about Korelitz: "I hope she's ready for all the angry tweets and emails."

Yeah, I think she probably is.

Korelitz's new novel is a smart, semi-satire about the reign of identity politics on college campuses today. That, in itself, is a tricky subject for a white novelist to tackle, unless she or he is a far-right conservative, which Korelitz is not.

But then Korelitz makes matters even more complicated. Her heroine is a Jewish feminist college president named Naomi Roth. Facing off against her are an African-American professor and a Palestinian undergraduate; these two men turn out to be the most "duplicitous" characters in the story.

You see why my student's eyes widened at what sounds like a deliberately provocative set-up.

Recently, the novelist Lionel Shriver stirred up a lot of criticism on the left by publicly denouncing what she called "tippy-toe" fiction constrained by identity politics. Korelitz is not tippy-toeing here; rather, she's asserting the novelist's right to imagine a story that's messier than a homily, and characters who are more nuanced than mere emblems.

Korelitz's setting is the fictional Webster College. Webster is an elite liberal arts college in the mode of Amherst or Williams. It used to be a bastion of old boys and old money, but it remade itself in the 1970s; now Webster boasts a much more diverse student body, along with a dining hall that serves culturally sensitive cuisine of all nations and a college portfolio divested of all trace elements of nuclear energy and diamond dust. And Webster has its first female president in Naomi Roth.

Naomi is our moral center and she couldn't be more likable: a single mother, astute and beleaguered, wild haired and a tad frumpy. She still harbors a lingering case of "imposter syndrome" under her proper Eileen Fisher outfits.

When the story begins, Naomi has become aware of a growing band of students— her own daughter among them — camped out around "the Stump," the epicenter of campus and the traditional gathering place for protests.

But this group of protesters is maddeningly close-mouthed, refusing to meet with the administration to discuss their grievances. At one point, Naomi talks with her friend Francine, the director of admissions at Webster, and Francine shrewdly characterizes this new mutation of campus protest in the Internet age. Naomi says:

"My door's been open for months. ... What kind of protest declines dialogue with its opponent?"

"A modern one," Francine said dryly. "These kids are not like we were. ... Interaction across the battle lines isn't what they're after. ... They want to represent something to their peers more than they want to gain respect from their opponents."

"Or accomplish anything," Naomi said, rolling her eyes.

"Oh, they're accomplishing plenty. They're compiling influence. ... "

"Gaining 'likes.' Getting 'retweeted.' "

"That's part of it. No point denying it."

One of the causes of the protest turns out to be the fact that a popular anthropology professor has been denied tenure; because he's African-American, students accuse Webster of institutional racism.

Naomi and the tenure committee have to remain silent for legal reasons, even though they know that the professor is guilty of something more damning than suspiciously high "Rate My Professor" scores complimenting his astronomically inflated grades. When a young student, a Palestinian refugee named Omar Khayal, emerges as the professor's most eloquent defender, the situation becomes so heated that Naomi has real cause to fear that she'll be ousted from the presidency of Webster.

The Devil and Webster is wittily on target about, among other things, social class, privilege, silencing and old-school feminist ambivalence about power. It also takes on Korelitz's home subject, the insanity of the college admissions process. But its central dilemma — whether we can form a cosmopolitan community where we affirm our individual identities, yet remain connected to one another — is, in realistic fashion, no closer to being resolved by the time we get to the end of the book.

“a fantastic finger-on-the-pulse-of-culture read”

“Jean Hanff Korelitz’s The Devil and Webster is a softer satire about the cultural upheavals now roiling our colleges. Identity politics, racial tensions, tenure controversies, student demonstrations and academic charlatans – all are explored. The story focuses on president Naomi Roth, a died-in-the-wool liberal, charged with turning the formerly conservative Webster College into a progressive institution. As Roth steers her institution through an increasingly menacing student uprising, she is forced to contend with many flash-point attitudes about higher education. This is Korelitz’s second campus novel (following Admission), and she clearly understands how colleges operate. Campus denizens will appreciate her descriptions of academic culture.”

The Wall Street Journal: rebirth of the campus novel

“The Devil and Webster,” Jean Hanff Korelitz’s sharp and insightful account of the current explosion of student discontent, ought to set off a golden age for the campus novel.

At an elite New England liberal arts college, students have occupied the quad, pitching tents and raising banners in protest of the administration. The source of their anger is the college’s decision to deny tenure to a popular African-American anthropology professor. Because the tenure process is confidential, the college’s president cannot discuss the reasons for the decision, and in the absence of an explanation, the protest movement has leapt to a damning accusation of racism. When a slur is discovered painted on a student building, the crisis comes to national attention. Supporters on the left call the president “a despotic figurehead,” while critics on the right suspect radical students of having manufactured the vandalism and place the blame for the unrest on the college’s “famously permissive mores.”

Given the contentious campus dramatics that now make the papers on a regular basis—the most recent and egregious being the violent attack at Middlebury College on the scholar Charles Murray and the professor who hosted him—everything in the above scenario would make a perfectly plausible news story. But, instead, it is the plot of Jean Hanff Korelitz’s “The Devil and Webster” (Grand Central Publishing, 359 pages, $27), a sharp and insightful novel exploring the current explosion of student discontent.

The college the book imagines is called Webster and its president is Naomi Roth, who first appeared in Ms. Korelitz’s 1999 novel “The Sabbathday River,” an updating of “The Scarlet Letter” focused on a young woman who is tried for infanticide. Roth is a dedicated second-wave feminist who has guided Webster’s transformation from a provincial institution to a celebrated bastion of progressive values. Ms. Korelitz has a keen appreciation for the irony that this onetime radical is now, for the protest group calling itself Webster Dissent—which includes the college president’s own daughter—little more than a symbol of systemic injustice. To students “within the magical prism that was time on a college campus,” Roth’s own history has no meaning—“only the great and wondrous *now *ever seemed real.”

Roth’s foil is the de facto leader of Webster Dissent, a Palestinian scholarship student named Omar Khayal, whose stories of childhood oppression and dangers faced have made him a kind of talisman to the impressionable and highly privileged student body. Roth tries to take a laissez-faire attitude to the demonstrations, but when she reaches out to Omar she’s rebuffed. Again, Ms. Korelitz hits on a trenchant observation about the nature of contemporary activism: Its object is not resolution but renown. “Interaction across the battle lines isn’t what they’re after,” a colleague tells the president. “They want to build their own constituencies. They want to represent something to their peers more than they want to gain respect from their opponents.”

What that something might be is never totally clear. Roth feels a parental affection for the undergraduates—just teenagers, she reminds everyone—who have become “divinely outraged” on behalf of a professor most have never met. Their vehemence is matched by the vagueness of their complaints, and Roth finds it hard to disagree with a friend’s assessment that, at the heart of it all, “young people need to feel their specialness. And one way they feel it is to transmute any kind of discomfort into outright oppression.”

As the stalemate deepens, Roth must handle the increasingly hostile protesters, the more reactionary members of the college’s board who want her to forcibly clear the quad and the media pundits eager to poach the crisis for succulent talking points. Ms. Korelitz breaks the tension with a clever plot twist that has the satisfying effect of making everyone, on both sides, look foolish and deluded.

“The Devil and Webster” is very much Naomi Roth’s book. In the midst of the furor, she undergoes a midlife coming-of-age, completing the switch from a person committed to challenging the rules to one whose duty is to enforce them. Hers is a memorable story, but it is just one from a setting teeming with dramatic potential today. The enclosed space of colleges has long offered writers an ideal laboratory for unloosing social conflict. Right now, the elements involved are especially unstable. This ought to be the start of a golden age for the campus novel.

THE WEEKLY STANDARD: A Campus Novel for the Age of Identity Politics

By Alice Lloyd

The campus novel is overripe for a renaissance. Because it will take a satirical rendering à la Lucky Jim—or perhaps dozens of them—to expose the painfully silly social politics of campus protest culture to the clarifying light of enough readers' wry, self-aware laughter. Unsurprisingly, few have dared to go there lately what with the risks of offending P.C. mores and triggering viral outrage probably outweighing the uncertain benefits of a literary insight.

It's all the more delightful, then, that in her latest novel, The Devil and Webster, Jean Hanff Korelitz—author of Admission and You Should Have Known—breaks ground in this richest of fields. She pits the thoroughly liberal president of a thinly veiled Dartmouth, Korelitz's alma mater, against a media-savvy student protest whose inarticulate aims this president craves to validate. Naomi Roth is the beleaguered leader of fictional Webster, a staunchly progressive New England college haunted by its very white, very male history.

(The book's epigraph quotes Daniel Webster's seminal 1818 defense of Dartmouth, "It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college. And yet there are those who love it!"—while its title takes us to the 1937 short story "The Devil and Daniel Webster" and Daniel Webster's fictional, Faustian defense of one poor soul to a jury of the damned. Webster, in the end, kicks the devil—a smooth-talking Mr. Scratch, no match for the great orator—from the New Hampshire courthouse.)

Naomi is Webster's first female and first Jewish president, a scholar of second wave feminism—the pre-intersectional, pre-LGBTQIA wave Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem rode—and, until recently, a popular Women's Studies professor. She distinguished herself to the board as the dean of women's affairs with her skillful handling of an unprecedented PR crisis: A student enrolled as Nell, and joined an all-female feminist affinity house to boot, only to matriculate already most of the way to becoming "Neil." A decade ago, Neil's presence in women-only housing posed an existential threat to the separatist feminism Dean Roth studied in her work and fostered, at least in theory, in her classes. It was as though her diplomatic management of students' and parents' concerns over Neil proved to the trustees and presidential search committee, quite believably, that Whatever weirdness may come, we need a highly competent hippie at the helm…

But once Naomi Roth made her full ascent to the presidency and had a few good years never feeling quite at home in the president's mansion, Webster College entered a climate in which the Neil crisis would have played out quite differently. She herself would become the target of a new type of student unrest, one that does not state its vague, intersectional aims so readily. Eradicating "like two centuries of impacted racism," as one student puts it, (or an eternity of transphobia, for that matter) doesn't begin such discrete "asks" as an audience with the president, so Naomi would learn.

Korelitz's novel shines for these subtle, artful framings, balanced on contextual details a reader lucky enough to be unfamiliar with the tessellating contortions of progressive campus discourse might miss. The story's central drama might as well have been drawn from fairly fresh headlines: A popular professor in a conveniently intersectional field—African-American folklorist Nicholas Gall, in the novel, who's failed to publish and plagiarized when he has—is denied tenure for these fully legitimate reasons trustees and administrators cannot reveal publicly. The unmanageable and inarticulate protest that erupts in response labels itself "Webster Dissent" and claims the school's intractable racist legacy as its source of outrage. An encampment, students in tents, shanties, and sleeping bags, colonizes around "the Stump." It's a literal tree stump but more so a symbol (just like Dartmouth's Old Pine) of swiftly broken promises to Native Americans unfulfilled from the college's founding until the 1970s, and a central meeting place for students, whom Naomi watches from her office window. The student leading the protest—he calls himself Omar Khayal and is a Palestinian refugee—is the shining apotheosis of righteous victimhood. And he's a friend and protégé of Professor Gall's.

Naomi, and not just because of the confidentiality restrictions shielding tenure decisions, can do nothing but "open her door" to the protesters and support the compassion, if not the logic, behind their dissent. (When it becomes clear they plan to camp out well into the winter—and the spring, as it turns out—Naomi has the college provide a "warming tent with heaters, blankets" and "the kind of toilet-trailer you found at your swankier outdoor wedding." Demanding they return to their dorms is just not her way; she brings the comforts of the twenty-first century dorm to them.) "Her heart went out to the them," and she sees herself in their struggle, even though she herself knows better. "The world would never work if people refused to perform this exact alchemy, to recognize that any injustice paid to one of them was paid to every one of them, and it was the duty of those who had a voice to speak for the voiceless," she believes. Naomi's daughter, a sophomore at Webster and a mainstay at the Stump, stops talking to her—and even becomes a spokesperson for the protest movement.

This struggle of Naomi's to encourage the students' stand against injustice and yet still maintain presidential authority, represents, Korelitz has said, the strained role of a former campus radical grown up to become the power that gets protested: "In this case the story was about a confrontation between a woman who considers herself ideologically in line with her own younger self and an enigmatic student who appears to see her very differently, and who forces her to rethink who she is and what she actually believes," Korelitz told Inside Higher Ed. What happens when radicals grow up and actually occupy positions of power? That was the question the novel began to coalesce around."

As an undergrad at Cornell, young Naomi Roth occupied the president's office to protest ROTC recruitment. Now that she's in charge, witnessing what children on campuses put themselves and their administrators through—this refusal to tolerate injustice anymore, the twisted expressions of which we on the right too easily ridicule, President Roth believes—stretches her love and patience for modern movement mentality. It's a modern movement mentality that's kept her daughter out in the cold for months.

A conversation between Naomi and her friend Francine, the admissions director at Webster, supplies a definitive summing up. Francine, who read all their essays, after all, observes that student protesters today don't care for the president's support. "They want to build their own constituencies. They want to represent something to their peers more than they want to gain respect from their opponents," she tells Naomi over a strained meal in student dining.

["…Omar] didn't answer emails. I did what I could, though I suppose I could have done more."

"Well…" said Francine. But she declined to make the expected noises. No! You tried so hard! "Really, what was I supposed to be doing? My door's been open for months. I've tried to get him to talk to me for months. What kind of protest declines dialogue with its opponent?"

"A modern one," Francine said dryly. "These kids are not like we were. You were," she corrected. "Interaction across the battle lines isn't what they're after. They want to build their own constituencies. They want to represent something to their peers more than they want to gain respect from their opponents."

"Or accomplish anything," Naomi said, rolling her eyes.

"Oh, they're accomplishing plenty. They're compiling influence. They're emerging from the crowd."

"Gaining 'likes.' Getting 'retweeted.'"

"That's part of it. No point denying it."

"Building their brands. Getting famous."

Francine shrugged. "Fame is power. Omar grew up powerless, remember. It's not like he's a Hollywood starlet. He has the entire Middle East to heal. Shouldn't we be helping him?"

We encounter a strange plot twist toward the end, before that a timely hate crime hoax, and even a meddlesome conservative professor emeritus on the board who leaks news of Gall's plagiarism to a right-of-center reporter (me, I imagine). All of these developments carry along the brisk action. But still my enjoyment of the The Devil and Webster was colored over by memories of Dartmouth College, unmistakably Korelitz's muse. Although she's lived in Princeton, where her husband is a professor, for decades—and other reviewers home in on whiffs of Williams (like Williams, Webster is not in the same athletic league as "the Ivies" but rivals them in U.S. News rankings, calling itself, cheekily, "The Harvard of Massachusetts")—no other New England campus strains against its demons just so:

Once a school of the richest, the WASPiest, the most loutish and most conservative of American men, and then later, after its extraordinary transition in the 1970s, the institution of choice for creative and left-leaning intellectuals of all genders and ethnic varieties. "A small school in the woods, from which, by the Grace of God, we might know His will" had been its motto in the early days, when Josiah Webster hacked his way north from King's College (later Columbia) to establish his Webster's Indian Academy beneath the towering elms. Two centuries later, with nary a Native American student in nearly that long, those words—like so much else about Webster—had been revised: "A small school in the woods, from which, by scholarship and thoughtful community, we might know the Universe."

I can't say for sure I would have enjoyed this book so much, in other words, if I weren't inescapably bound to swap in Dartmouth's Eleazar Wheelock for Josiah Webster, the Old Pine for the Stump, the former Indian mascot for… the former Indian mascot. Or to read Dartmouth's thirteenth president, Hungarian-American John G. Kemeny, for the Franco-Armenian Webster president Oksen Sarafian, whose progressive vision changed everything the moment he arrived on campus in 1966, and whose guidance Naomi desires from the depths: "She wished that Oksen Sarafian were still here to be walked around the campus, introduced to what he'd made, and to the Jewish female (feminist!) scholar who now sat at his old desk. She wondered how he'd be handling the kids out at the Stump. She wished she could ask him." Sarafian, as with the non-fictional Kemeny, admitted the first women and inaugurated the reparative Native American studies program—now, just like Dartmouth's, among the nation's finest. (When Korelitz arrived at Dartmouth in 1979, Kemeny was two years from retirement.)

Maybe it takes a woman of Dartmouth, after all, to look out on a generation of protest-crazed college students and see nothing new under the sun—and to say so, sharply but lovingly, in crisp satirical terms. There's something about four years in those rugged wilds caught (as Dartmouth still is, and "Webster" too) between the old guard that still hates to see a single frat close and the frantic, progressive march toward an amoral emptiness based, in the novel, on a what turns out to be a remorseless lie. But it takes a grown-up radical's steadiness, in Korelitz's telling, to kick the devil from the courthouse.

Publishers Weekly

Korelitz (Admission) raids the current news climate for this hot-topic read about diversity, protest, and “liberal idiocy” on the campus of progressive Webster College, headed by its first female and Jewish president, Naomi Roth, a feminist academic with her own radical past. Roth’s pride in Webster’s evolution from white male homogeneity to carefully culled inclusion is tested by the denial of tenure to popular black professor Nicholas Gall, which spawns a massive student movement to protect him led by Omar Khayal, a charismatic Palestinian student. Though Roth prides herself on speaking “truth to power,” when she is the “establishment” her words fall on deaf ears. They fail to impress even her own daughter, Hannah, a member of the protest movement; best friend, Francine, the college’s admissions dean going through her own academic crisis; and the restive college board. There’s much to ponder in this dense political and social debate, and it’s as overwhelming to Naomi as it is to readers, who, though pitying her no-win situation, can see the hypocrisy that blinds her. Ultimately, it isn’t the political twist that’s so riveting in Korelitz’s morality tale, but the apolitical, ageless struggle of a mother letting go of her daughter, a fact “so very ordinary, but... everything, too.”

National Book Review

What happens when a student protester at an elite New England college grows up and becomes its first female president? Jean Hanff Korelitz answers that question and more in this compulsively readable, uncanny, and irreverent novel that focuses on an American college campus to expose our current national psyche. Korelitz — author of Admission, a college-admissions novel that was made into the 2013 film starring Tina Fey and Paul Rudd, and You Should Have Known, about a New York shrink who learns her husband of two decades is a sociopath — is an expert on the art of deception, a talent she puts to excellent use in her latest book. In The Devil and Webster, she churns the college melting pot to explosion by adding, among other things, a polarizing Palestinian campus leader and a controversial tenure case complicated by a secret.